Part 3

by Yves Jaques

We say a few parting words, get in the Rover, and tread slowly down the worn road.

"You see what I mean," says Foraker, "what gold fever can do to a man. Lost his house, his wife, his children. Digging on his claim with no rhyme or reason, and no money to do it right. Crazy."

We all shake our heads in grave sympathy. Foraker’s meaning is clear, we are beyond this kind of thing. We are intelligent, rational men, engaging together in a sound business enterprise.

We leave almost immediately in a four-wheel Rover. It turns out that the refinery is actually just over the state border in Arizona, a little town called Oasis. As we drive the endless desert, I begin explaining to my Uncle the many reasons why the contract is a joke. "First of all," I tell him, "it’s not even set up for a notary. A contract like this definitely needs to be notarized. I mean, have you seen this guy’s ID? A notary is a good, non-threatening way to do it. If he’s legitimate, it shouldn’t be a problem."

"But you don’t understand, Yves," replies my Uncle. "This is an agreement between gentlemen. The contract is a formality. I know this man."

I see him staring excitedly out the window at the low, dry hills. He’s never seen the desert before. He’s never seen this much desolation. He’s taking pictures with a top-of-the-line Nikon. He’s not even listening to me.

Before I’d left Denver to meet my Uncle in Las Vegas, I’d set-up an appointment with a contract attorney in Las Vegas. I was looking out for my Uncle. He was after all my favorite Uncle. The one who lived in a converted farmhouse, and had a loft full of instruments. This was the man that had blown up a baby carriage with home-made black powder. I love this man.

Coming from a less attorney plagued society however, Pierrot pooh-poohs the idea of meeting with this attorney. Given the brevity of the contract, he has a point. But I still try and convince my Uncle. I’m thinking that maybe he’ll listen to an outside party, someone who really knows contracts. The attorney will tell him he’s insane.

As we drive across the border, over the stylish Hoover dam with its gorgeous art-deco angels, I stare at the transmission lines climbing vertically out the canyon’s mouth. That’s my Uncle. That’s my family. Stubborn as hell.

**********

After getting fired by the new owner of his Father’s music-box factory, Pierrot had cast around desperately for new employment. The baby of the family, he’d been coddled his entire life. Suddenly, in his mid-thirties, with a house, a wife, and three children, he’d been let out into the wilderness.

Responding to an ad in the paper, he’d come home one day after months of joblessness with a brand new cargo truck. He’d spent the last of their money.

Even after he explained himself his wife remained furious. A Swedish manufacturer of office furniture was just moving into the Swiss market. The ad Pierrot had responded to was a call for independent short-haul drivers to ferry and install office furniture around Switzerland. He’d bought the truck knowing nothing about the company, and little about the prospective delivery job.

His wife told him he was insane. His Father told him he was insane. Everyone in Ste. Croix told him he was insane. But ten years later, he was a regional distributor, with a group of drivers reporting to him. He’d made it. In the face of everyone’s criticism, he’d persevered and made it.

This was the psychological history that was working on him now. Just like ten years ago, everyone was telling him he was insane, that this could never work. He was going to show them once again. And become truly rich this time.

At last, Foraker pulls in at a desert pit stop. There’s a restaurant, a garage, a gas station, and a few scattered mobile homes with large air-conditioners strapped to their backs. I notice the sign atop the restaurant reads "The Oasis."

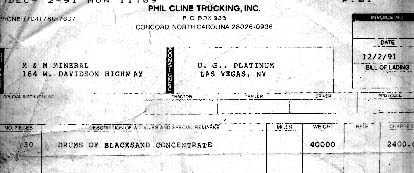

Foraker turns to my Uncle and I, sweeping his hand expansively. "Well this is it guys, Oasis, Arizona. U.S. Platinum Refinery owns this whole place."

We grab a lunch at the dowdy, forgotten diner by the side of the desert highway. This is Oasis. I’m watching my Uncle. I can’t believe the squalor of the thing has no effect on him. Never having been to the United States before, he has no yardstick to measure by.

Fifty paces behind the restaurant sits a typical pre-fab metal warehouse. In the lot to one side of the building stands a collection of abandoned construction equipment, baking in the noon-day sun. Foraker has a monstrous set of keys on a fat silver ring. He tries them slowly, methodically, rejecting them one at a time. His consternation grows as he continues to fail at unlocking the small side door to the warehouse.

My Uncle and I stand staring off at the low red-brown hills, in an attempt to appear unconcerned. Finally Foraker turns to us. "Damnit, I just can’t believe it. I don’t have the key for the warehouse. The damn thing must be at home."

My Uncle queries me in French, "He doesn’t have the key?"

"Correct," I say, a bitter smile on my face edging the look of triumph in my eyes. I’m sure that this will put my Uncle over the top and back into reality. "He says that he left it at home."

"A shame there’s no windows to the warehouse," says my Uncle.

"Indeed," I say.

As we drive back to Vegas I convince my Uncle that there is one sure way to test Foraker’s legitimacy, we have to go to North Carolina and visit M & M Minerals, the supplier of the raw ore. He’s come this far, why not take the final step? If these guys check out as legitimate, the whole thing looks much less hazy. My hopes soar when he agrees that we should go. I feel for the first time that Pierrot is listening to reason.

I explain to Foraker that my Uncle thinks it’s necessary for he and I to visit the ore supplier in North Carolina. Again, Foraker doesn’t seem to like the change in plans, but agrees with little protest, telling me to call him at his home when we’ve settled our travel arrangements.

Back at the Excalibur, I secure plane tickets, and with a heavy heart cancel our appointment with the Vegas contract attorney.

The following morning, we are in Charlotte, North Carolina.

**********

M & M minerals is located in Concord, a small town about an hour out of Charlotte. The weather is superb as our rental car shoots us down the byways in comfort. A few wrong turns righted, and we find ourselves winding down an ancient gravel road that occasionally passes the detritus of a bygone mining age, broken vehicles and equipment strewn haphazardly along the banks of a placid river.

The road terminates abruptly at a two story industrial structure with a tin shack tacked to its rump. A couple of geezers saunter out to greet us. Introducing themselves as Mike and Charlie, they are warm and friendly, very unassuming in their manner. I’ve done enough selling to quickly sense that these guys are legitimate; either that, or highly trained method actors. As they show us around their operation, I discard the latter. They know this place and its history far too well. These guys are on the level. I’ve been trained to sense when people are lying. I sell real estate. People lie to me the live long day.

Their story is a wonder. This area of North Carolina was mined extensively for gold in the Nineteenth Century. The river we stand next to was once laden with gold ore. All the high grade ore was mined long ago, but the river rock still contains measurable quantities of gold and other precious metals.

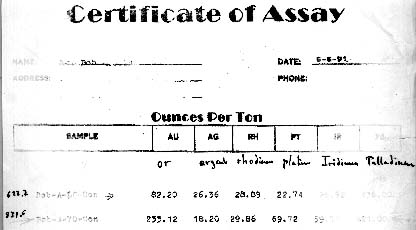

Mike and Charlie show us around their elaborate set-up. First they pull up river rock with a backhoe and run it through a crusher. A conveyor takes it over to the main building where the crushed rock is ground into sand. This sand is then run through a Rube Goldberg contraption of their own design (they are both retired engineers) which runs on electrostatic principles. This machine, over multiple passes, separates the metallic particles from the non-metallic. They eventually end up with what they call ‘concentrates’. Mike and Charlie claim that they’d had their ‘concentrates’ analyzed by a local university, and that the content of gold, platinum, palladium, and rubidium was almost enough to make the refining of this black sand commercially viable.

‘Almost’ being the key operand. There still wasn’t enough precious metal in the sand to make refining it worth the effort. At least not until precious metals made another jump in the market. So they’d been stuck with their black sand not knowing where to turn. That is, until Billy Jerry Foraker came along.

As far as Mike and Charlie are concerned, the man is a saint. The first time that he’d visited them, he’d taken samples of their ‘concentrates’, and had them assayed back in Nevada. Convinced of the feasibility of refining the material, Foraker had bought $5,000 worth, and contracted to buy as much as they could produce.

"He used to work for DuPont, you know," says Charlie with a glowing expression on his face, as we sit at a local restaurant and discuss mining over eggs and browns.

"He’s had a long and profitable career in mining," seconds Mike. "He was a chemical engineer you know, but he just couldn’t take all that bureaucracy at DuPont."

"Big company," says Charlie.

"Yep, big company," says Mike.

I start feeling pretty damn well confused. Maybe I’ve been misjudging this Foraker guy. Hell, he knows a lot of mining people. No one seems to think there’s anything funny about him. These Carolina coots are definitely legit. The man is supposedly a chemical engineer. New manufacturing processes are constantly being devised. Why can’t it be true? Maybe I just judged him on his musky cologne, and his pool shark feel. After all, I’ve been raised Swiss. Down deep I can be fiercely xenophobic. Maybe I’m wrong.

**********

"Putting the mark into the con man’s play apparently has another significance, one which joins sociological and economic vocabularies. A player is one who is necessary to a play...the mark’s irreplaceability is not just asserted but demonstrated." So writes Leff in "Swindling and Selling."

With swindles that rest on new products or processes, there’s another way that the sophisticated swindler obscures the nature of the con. He finds legitimate but misguided inventors/engineers/designers to whom he attaches himself. Their belief in themselves (and the con man) is tremendously strengthened by the con man’s (posing as an investor) interest. They become convinced that their idea or product, whose miraculous claims have heretofore fallen on deaf ears, has finally found an audience. Their effusiveness and honesty then attach to the con man, plating his con with an armor of sincerity.

The "Casby Craft" swindle makes for a classic study of this type of con. Casby was a physicist by trade, but his true love was boating. He thought he had a revolutionary design for a sailboat that could cut manufacturing costs in half. He found a ready ear in Fred Miller, an LA con man posing as a businessman and boat lover. Using Casby’s enthusiasm, Fred Miller quickly amassed a group of excited investors, who spawned in their turn a second wave of investors. Miller paid a few college students to do some bunco designs, and built a scale-model of the boat, but the supposed prototype that "Casby Craft" was building was never even commenced.

It was the innocent Casby’s enthusiasm that propelled and legitimized the scam. Miller almost made off with a quarter million profit, when by a piece of personal misfortune, a curious investor discovered an empty shipyard where the prototype was supposed to be under construction.